People are refusing to wear masks during a pandemic. Why? To understand, we rewind to the “Anti-Mask League” of 1919 and to the opposition to seatbelt laws in the 1990s. Then we answer the big question: If people won’t listen to mandates, what *will* they listen to?

Jason Feifer: This is Pessimists Archive, a show about why people resist new things. I'm Jason Feifer. The people of San Francisco were excited. It was November 21st, 1918, and this was to be their day. Their day of freedom, their day of victory, and it would all begin at noon. So, as the golden hour neared, they gathered in the streets in front of clock towers and watched and waited. It must've been a little like new year's Eve in times square, except with big hats that nobody thought were ironic.

You could imagine them counting down the time, 11:58, 11:59, and then, the clock struck noon. And the people of San Francisco we're able to take off their masks. Because this was the hour when San Francisco's mandatory mask law ended and it marked the end, it seemed, of the whole Spanish flu situation. The fluid had hit San Francisco hard the month before. Businesses were shut down and people were instructed to wear masks, which they did. But now, with the law expiring, people were excited to uncover their faces. Here's how the San Francisco examiner reported it the next day.

Voice Clip (San Francisco Examiner): Five minutes after the hour, 95% had dumped their masks and were laughing back at the sunlight and into one another faces as if they had just made a great and delightful discovery.

Jason Feifer: The city had asked residents to deposit their masks at convenience stores so they could be gathered up and used as surgical gauze, the hospitals were running a shortage, but nobody remembered to do that. Instead, they threw their masks on the sidewalk, or they hung them on the front of an ice cream truck that was nearby. By 12:15, some newsboys saw a man walking by still wearing a mask and they chased him chanting, "Take off your mask."

Crowd: Take off your mask. Take off your mask. Take off your mask.

Jason Feifer: In the San Francisco examiner right next to the news about all this, the writer Annie Laurie piled on the cheer.

Voice Clip (Annie Laurie): The war is over. The flu is conquered. Our masks are off. Come, altogether now, smile, smile, smile. And with that smile, conquer fear, and down pain, and shake distrust. This is the day of the smile.

Jason Feifer: But of course, as we know now, the smiles did not last long.

Gary Kamiyah: That was a big deadly mistake, and they had what we now call the second wave.

Jason Feifer: That's San Francisco historian, Gary Kamiyah. These days, of course, we all know about the second wave of the Spanish flu. That wave of sickness and death that came after everyone thought the virus was gone. And once the second wave struck, as you might imagine, a second mandate to wear masks went into effect. And that is when San Francisco got a second, far more assertive, movement against the masks.

I mean, the first time people were forced to wear masks, they complied and then they partied in the streets when the mandate was over. But the second time, that is when people organized...

Gary Kamiyah: The Anti-Mask League.

Jason Feifer: My phone connection with Gary wasn't the best. So, just to make sure you heard that right, he said "The Anti-Mask League." As in, an organization against masks that called itself the Anti-Mask League. It was formed in January of 1919.

Gary Kamiyah: And they had this notorious mass meeting where they had 2,500, in different numbers, could have been as many as 4,000 people, meeting in an auditorium.

Jason Feifer: They did not want to wear masks. They were done with masks.

Gary Kamiyah: The Anti-Mask League began to educate, and they actually, no doubt, played a major role in the resending of the mask law on February 1st.

Jason Feifer: And so, it seemed they liberated people's faces to breathe in that fresh virusy air. This story may sound familiar today and for a few reasons. I mean, obviously first, there is an echo of it in our own world right now. As I record this in May of 2020, medical experts fear that our own second wave is coming and our own protesters are outside of state capitals. And also, it's possible that this story is familiar, because you've actually already heard about the Anti-Mask League of the century ago, NPR reporter, Tim Mack, unearthed it in a now viral Twitter thread recently, and it caused a wave of media attention.

For example, the Washington post had this headline, "Coronavirus mass confrontations echo San Francisco's Anti-Mask League a century ago." And time magazine ran with this, "1918's warning for coronavirus shut down protestors." Now, these stories all play towards the same point, that the Anti-Mask League was foolish and led to more deaths.

But the thing is, we shouldn't just shake our heads and say, "Oh, those dumb people." And we shouldn't resign ourselves to repeat history either. Because there is actually so much to learn here, far more than any media outlet that I've seen has given it credit for. The Anti-Mask League isn't just about people being dumb, it's not even, maybe, about people being dumb at all, it's about human psychology. And if you want to understand how to change people's behavior, then these days there's really no better place to start than with the Anti-Mask League.

Because there's a name for what's happening here. It is a well-known, well-documented, often repeated phenomenon and it is called, reactants. Here's Wharton marketing professor, Jonah Berger.

Jonah Berger: Psychological reactance is a negative emotional state that we feel when we feel like we are not in control of our behavior.

Jason Feifer: People don't like losing control, even if it's good for their health. So the question is, how do you give them control and still get them to do what you want? That is the question I want to explore on this episode of Pessimists Archive, because it is a critical one right now. These are complex times and they will not be clarified by simplistic anecdotes. So, it is time to take a trip into psychology, into marketing, public health, and after all that, we are going to get into the real history of the Anti-Mask League. The one that Gary says everyone is missing.

Gary Kamiyah: There's been a lot of really poor reporting, and sensationalist reporting on the mask laws that's simply factually wrong.

Jason Feifer: So, let's get it right. And it's all coming up after the break.

fs

All right. We're back. I know I just made a pandemic-sized promise to you, to draw some giant lessons from this tale of people not wanting to wear masks. Let's waste no time getting into it. And we're going to start by going back to Jonah Berger.

Jonah Berger: I'm a marketing professor at the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, and the best-selling author, most recently, The Catalyst, How To Change Anyone's Mind, as well as some prior books, Invisible Influence and Contagious.

Jason Feifer: And when I told Jonah about the Anti-Mask League, he said, "Yeah. That's a great example of reactants." The word reactants describes that negative emotional reaction. If you're at work and your boss says, "Here's the plan. And here's what you're going to do." Then you immediately start thinking about, why it's a bad plan, and why you don't want to do it, and why it's not going to work. And that is reactants. You are experiencing reactants.

Jonah Berger: We have a drive for freedom and autonomy. We like to feel we're in charge, we're in the driver's seat of making our decisions. Anytime we feel like someone else is trying to persuade us or shape our behavior, our actions, our attitudes, we essentially put up an anti-persuasion radar. And you can almost think about it like an anti-missile defense system, or like a spidey sense, if you will, that goes up when we feel like someone's trying to persuade us.

Jason Feifer: And this is built deeply into us as any parent knows. I mean, have you ever told a kid to stop doing something? Here's us at dinner last night, trying to get our five-year-old to stop putting his feet on the table.

Speaker 7: Nope. Not okay.

Jason Feifer: No offense. Stop putting your feet on the table.

Speaker 8: This is what I do.

Jason Feifer: I mean, I got to hand it to him, "It's just what I do" is indisputable fact. And Jonah says, "It's also not such a bad thing."

Jonah Berger: The same processes that drive our behavior when we're young, also shape our behavior when we're older, they're just a little bit more complex.

Jason Feifer: I mean, reactants helps us avoid scams. It's why every advertisement doesn't drain our bank account and why we can develop into leaders and critical thinkers. Reactants can create overconfidence, which can be totally off putting, of course, but also, who would start a world-changing company, or an ambitious new restaurant, or whatever, despite there being a high likelihood of failure, if it wasn't for some kind of overconfidence.

How many entrepreneurs have said some version of, "If you tell me I can't do something, then I'll do it twice." Well, that's reactants. The problem is that, although reactants can help us stand out, it can also leave us blind to good ideas. Because not all persuasion is bad. You really should keep your feet off the table. And protective measures during a pandemic are not the only time that people have pushed back against things designed to protect them. Okay, we'll come back to Jonah Berger in a second, but do you know the history of people opposing seat belts? It goes back to the 1930s.

Dan Albert: There's a plastic surgeon in Detroit stitching up faces and he notices that, "Hey, this gash on this forehead looks exactly like this radio knob on this Chrysler."

Jason Feifer: That's historian Dan Albert, author of a book about automobile history called, Are We There Yet? And this plastic starts telling car companies, "Hey, people are slamming their faces into your cars." And that's where you start to get things like padded dashboards. But from there, automakers were generally resistant to adding safety features, because they were expensive and they would remind people of how unsafe a car could be. And also, people just didn't want a lot of this stuff. Just straight up, didn't like it.

In the 1940s, surveys of drivers said, "No. Do not put in seat belts. In 1956, Ford came out with a car that did have a seat belt and it advertised all of the cars safety features, and sales tanked. In 1968, the federal government forced car companies to include seat belts, and it barely mattered because only 5% of drivers actually used them.

Dan Albert: They are just tucked behind the seat and nobody's buckling up.

Jason Feifer: In 1974, the government passed a law mandating something called an interlock, which is to say the car wouldn't start unless seat belts were buckled. People, absolutely, revolted against this. They flooded Congress with complaints and lawmakers scrambled to pass a new law and that was the end of the interlock. In its place, a car could buzz to remind you to wear a seat belt, but only for a maximum of eight seconds.

Dan Albert: And that's my favorite, because, in a car today, the buzzer can only last eight seconds.

Jason Feifer: What? I mean, I know that cars beep when you don't have a seat belt on, but only for eight seconds and that's by law. Okay. Let's grab a timer and see about this. Okay, here we go. Two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight. Exactly.

"Well, Senator, after millions of dollars spent to win re-elections and years spent entrusted with the men's power and responsibility, what did you accomplish for the American people?" "Well, I made sure cars can't tell you to be safe for more than eight seconds." Well, how about that? Then in the 1980s, Senator Elizabeth Dole struck a deal with the auto companies. They really, really didn't want to install airbags. And so she said, "Okay. We won't force you to, but in exchange you have to lobby states to pass mandatory seat belt use laws."

So, the companies did, and the state started to pass them, and they made these arguments about how wearing seat belts were a greater public good and highlighted stories about people whose lives were saved by seat belts, and oh boy, people were pissed. Here's from a letter to the editor I found, the Berkshire Eagle of Massachusetts from 1994.

Voice Clip (Berkshire Eagle): I do not, for an instant, believe any slanted statistical evidence presented by their side. And I am sick unto death of hearing this public burden theory, or that story of the child saved by the seat belt. If I wear my seat belt, it's because it makes me feel safer. But some faceless Yahoo in a suit in Boston may not legislate my safety by coercion.

Jason Feifer: And is that not a fascinating piece of writing? It was signed by a guy named David Vuitton. And okay, let's consider what David just wrote there. He does believe that seat belts make him safer, but he still sees seat belts as something pushed on him and based on lies. And that is such a beautiful example of reactants, the psychology term we were talking about a moment ago, and I got to wondering, how long does reactants last in a situation like this? What does David think about seat belts now, all these years later? Now that they're common and most people wear them? And the emotions around the issue of died down? Does David wear a seat belt? So, I did a little Googling, and some social media stalking, and I sent a lot of emails, and, do you remember writing that letter?

David Vittone: If I read it in my tone of voice, I can hear that guy. But no, I have no recollection of writing that at all.

Jason Feifer: Still, there is no question it was him.

David Vittone: I mean, I write 10 letters a week, they print one. I'm just that kind of guy. Troublemaker.

Jason Feifer: Dave is a musician who's usually out playing gigs. But of course that's all gone these days. So, he had plenty of time to chat. And honestly, I liked talking to him he's funny, and self-deprecating, and never runs out of things to say, and at his very, very core, he hates being told what to do. Okay. Let's talk about seat belts. He lives in a remote part of Massachusetts and it is miles from his home to the nearest main road. And he will not wear his seat belt on those back roads just to stick it to the man. Even though he has been in car accidents on the main roads, which is where he does wear his seat belt.

David Vittone: Yeah. I was airborne, head-on collision and airborne glass, I'm like this, "Aah." And right to the stop, the seat belt holds you in the seat, and lap, and shoulder belt, I'm like, "Wow, it works." That was exciting.

Jason Feifer: What's the moral of that story? The moral of that story is that the seat belt saved your life.

David Vittone: Maybe. Well, it saved me from injury. But I'm annoyed. I have a finely tuned hair trigger sense of outrage.

Jason Feifer: So, I wondered, back in 1994, was there anything the government could have done to not trigger that sense of outrage in him and still get him to wear a seat belt? What do you think was the better thing for the government to do in that situation?

David Vittone: I really don't know. Because all I know, as a child I could ride facing backwards in a station wagon, I can't do that anymore. I could ride in the back of a pickup truck bed. It's no more, or less safe, or dangerous now than it ever was. And you can't do that any more.

Jason Feifer: He just went on like this for a while, recalling all the freedoms that he felt he once had that he doesn't anymore. But the short answer is this, he doesn't, exactly, have a governmental solution, but he says that he'd be more willing to wear a seat belt if they didn't force him to do it. And this is interesting, because if you were so inclined to argue with Dave about this, you could have a long argument. You could argue about greater good, or public safety, and Dave or someone like him, could argue about personal liberty and the role of government. And I get it. This can be philosophical, and political, and ideological, and it could get there very fast, for seat belts, and masks, and anything else you wanted to throw into the big pot.

But my point is not to engage with any of that here, because those are bigger and stickier than the very human question at hand. And that is, if you are in the position of trying to create change, to change people's behavior, then what do you want to do here? Do you want to argue with Dave, even though there's no argument that will ever convince him to change? Or do you want to do something else? Do you want to find another way? Because there are other ways to change people's behavior. And this brings us back to Jonah Berger, the Wharton marketing professor, because...

Jonah Berger: One of the simplest ways to think about it is to give people choice. At its core what drives reactants, is people don't feel like they're in control. And so, any way you can give that control back, rather than trying to persuade people, let them persuade themselves, they're going to be more likely to go along.

Jason Feifer: A simple example is this, great presenters will often give people two options. You can do A or B. If they only told people to do A, people would think of all the reasons they don't want to do A. But if you give them A and B, then people sit and think about which one they like better. Or you could step it up and not give them any options at all and instead you let them create the options.

Jonah Berger: I was talking to a startup founder who wanted people to work hard and stay after work. Then of course, when you tell people, "Hey, you need to put in more hours." They say, "Ah. No, thanks. I'm not really interested." So instead, he had a meeting. And in that meeting, he said, "Hey, what kind of company do we want to be? Do we want to be a good company or a great company?" Now, you know exactly how people answered that question, "We want to be a great company." And then he says, "Okay. Well, how can we be a great company?"

And people start throwing out ideas, and one of them is, they need to work harder. And then later when he comes around and say, "Great. That's a great suggestion. Let's do it." It's going to be much harder for people not to go along because they came up with the idea themselves.

Jason Feifer: But, how do you do that at scale? Because if you're trying to shift the behavior of millions of people, say, to get them to wear seat belts in cars, or masks in a pandemic, then you can't do it all by Town Hall. And so, Jonah offered two courses of action here, with great examples. The first is, highlight the gap.

Jonah Berger: So, rather than telling them what to do, point out a gap between their attitudes, and their actions, or what they are doing and what they might recommend for someone else.

Jason Feifer: For example, Jonah told me about this amazing anti-smoking campaign in Thailand. The government had been telling people not to smoke, but that wasn't working. So, they hired the advertising from Ogilvy Thailand who executed a brilliant idea. They sent children out onto the streets, holding a cigarette. Then with a secret camera rolling, the kid would find an adult who smoking and walk up to them and say, "[foreign language 00:20:28]?" That's footage from the advertisement that was eventually made out of this.

So, the kid is saying, "Can I get a light?" It's the thing that adult smokers will say to each other all the time. "Can I get a light?" And in response, the adults all start lecturing the kid. They say, " [foreign language 00:20:49]." One man here is saying, "If you smoke, you die faster. Don't you want to live and play?" And another says, "You know it's bad. When you smoke, you suffer from lung cancer, emphysema, and strokes."

And then, here comes the gut punch. Once the adult is done talking about all the ways that smoking is bad, the kid hands them a card and walks away. So, the adult opens the card and reads it. And it says, "You worry about me, but why not about yourself?" This ad had a huge impact. It almost immediately led to a 40% increase in calls to a Thai agency set up to help people stop smoking.

And it's because of that thing Jonah said, "Highlighting the gap." Showing people the distance between their attitudes and their actions. And here's the second way to change behavior at scale. And that is social influence.

Jonah Berger: There's a great campaign in the UK, for example, where some set of people aren't paying their taxes on time, and so, they send out a letter just letting people know, who aren't paying their taxes, that most of their peers pay their taxes. And that greatly increases the rate of compliance.

Jason Feifer: Similarly, the utilities company, Opower got people to use less energy by including a little note with people's bills that said stuff like, "Hey, your neighbor is using 50% less energy than you." This way you're never really telling someone what to do, you're just giving them information that makes them reconsider their own actions. So, knowing all this, I wondered, during this pandemic, has Jonah seen anything coming out of state, or federal governments that he thinks has been an effective method of influencing behavior without triggering reactants? And he said, "No."

Jonah Berger: Public health officials and government officials think it's all about information. And while information is useful, sometimes, that often isn't the biggest driver of behavior.

Jason Feifer: Which is a depressing statement. Because, I like information, I'm here providing information right now, but it reminds me of what we learned talking to Dave about seat belts. You can have a logical argument all day long, if you want to, and of course, I think that's what a lot of people seem to just want, they just want to argue, but if the goal is to actually change behavior, not change people's attitudes or their core beliefs, or how they feel, just change the behavior, then you have to start from the understanding that arguments and mandates and information won't work for a lot of people.

So you might as well try something else. And what else is there? It is now time to tell you about the real history of the Anti-Mask League of a century ago, which is actually a really complicated history of how not to fight a pandemic and what we should do, but probably can't do instead. And it's coming up after the break.

All right, we're back. It's time to get into just what was motivating The Anti-Mask League. And it's important to understand this, because, like I said, the Anti-Mask League has been used to draw all sorts of parallels to today. Here are a couple more headlines to give you an idea. A post on forbes.com said, "Protesting during a pandemic isn't new, meet The Anti-Mask League of 1918." And in a story that featured the Anti-Mask League, NBCNews.com said, "San Francisco had the 1918 flu under control. And then, it lifted the restrictions." But just what is the lesson of the Anti-Mask League?

It is more complicated than it sounds. Before I started reporting this episode out, I kept wondering this question. Aside from just the simple fact of people not wanting to be told what to do, what else might have been behind a thousands of people refusing to wear masks during a pandemic. And then I remembered something I'd read once. It was a piece about how frustrating it is to work in the field of prevention, because you have to constantly struggle to get financial or political support.

Kevin Haggerty: Well, it's always hard when you think about demonstrating the impact of prevention to convince people of something that didn't happen.

Jason Feifer: That's Kevin Haggerty. A professor at the University of Washington School of Social Work, who directs a research group that's focused on the science of prevention. And I mean, think of it, if you're a politician deciding where to throw your support or where to direct resources, prevention doesn't have a lot of payoff for you. Prevention requires money and effort. That's money and effort that could have gone somewhere else.

People must sacrifice in some way for prevention, which means sacrificing for the absence of something. Something you can't see and that's very hard for a politician to get credit for. I mean, it's nearly impossible to say, "Hey, a bad thing didn't happen to you because of me." And also keep in mind that prevention doesn't necessarily mean elimination. It could just mean lowering the rate of something.

So now, imagine trying to say, "Hey, a bad thing happened, but thank me because it could have been worse." And also, for what it's worth, many people just don't believe that prevention is even possible.

Kevin Haggerty: I work in the area of substance abuse prevention, and for many years people didn't really believe that you could, actually, prevent things like substance misuse or teen pregnancy.

Jason Feifer: If you ask people if drug abuse or teen pregnancy is a big problem, Kevin says that they say it is. They say rates are up. But not true. Prevention has worked. They're both weighed down. So how do you actually get people to buy into prevention? Well, Kevin offered two ways. One is leadership. If leaders buy in and even participate, that makes a difference, he says. And on the question of masks today, well, you've seen, shall we say, some mixed messages from leadership. And the other thing you need in order to grow support for prevention is data.

Kevin Haggerty: It's really pretty hard to convince people of the impact of prevention without having really strong longitudinal randomized controlled trials.

Jason Feifer: That might sound like a contradiction with what Jonah, the marketing professor, said a moment ago, about how information isn't always convincing to people. But I think the two actually go hand in hand. Because the thing is, smart communication may bring people in, but they won't stay if they don't like what they see. They need to see something that feels convincing. And we do not really have convincing with most masks. The podcast Science Vs did a great episode, breaking down the science of masks, explaining that we do have some good studies showing that surgical masks can stop virus transmission. But of course, those aren't the masks that most people have access to, or even should have access to, given the shortage for healthcare workers. Here's host Wendy Zuckerman, from that show.

Wendy Zuckerman: Frustratingly, we don't have studies like the ones we just talked about for cloth masks. The research just hasn't been done. Which is a big reason why we have the great mask war going on over cloth masks.

Jason Feifer: No leadership buy-in and no research. Basically, people are being asked to cover their faces today with whatever they have, as a way to improve some uncalculable odds. And that is a pretty good setup for this. So take me to the flu of 1918, in San Francisco.

Gary Kamiyah: Yeah. So San Francisco was very hard hit by this horrifying epidemic, and unfortunately, they didn't react as quickly as some other American cities.

Jason Feifer: This, again, is Gary Kamiyah, the San Francisco historian we heard at the beginning of the show. He's the author of, Cool Gray City of Love: 49 Views of San Francisco. And he writes a history column for the San Francisco Chronicle. Now remember, the Anti-Mask League of San Francisco, that he's telling us about, formed in January of 1919, but the flu first reached San Francisco a few months earlier in the fall.

So, to understand where these anti-maskers were coming from, we need to see what led up to them. And let's start in October of 1918. The city is hit hard and reacts late, schools and businesses were finally shut down to the middle of October. But the centerpiece of the city's response, the thing that they really put the bulk of their messaging and faith into was unusual.

Gary Kamiyah: They thought the masks were more effective and made them the center piece of their efforts more than any other American city.

Jason Feifer: Masks weren't really a thing across America, at that point, though, they were more popular on the west coast. That's because a well-known doctor named Woods Hutchinson had traveled up and down the coast proclaiming that masks were nearly foolproof way of avoiding the flu. At first, San Francisco just suggested that people wear masks, but by late October, they were mandating it. And here's the thing, people wore them. And they generally wore them without protest, because of something else, entirely unrelated. World War 1 was still going on and fighting the flu became acquainted with the war effort.

Gary Kamiyah: It was your patriotic duty to wear a mask. And if you didn't wear a mask, you were a slacker, as the expression was called, [inaudible 00:32:10] out on the front lines with the boys, but you were at home and you had to do your duty.

Jason Feifer: But despite that, confusion soon reigned. In late October, newspapers around the country reported that the surgeon general of the United States, as well as other top medical authorities had declared masks to be harmful. A telegram statement from them had apparently said...

Voice Clip (telegram): There is no virtue in the masks. Rather, they are a detriment under the free breathing into the lungs of plenty of pure air and sunshine. The real antidotes for sickness of any kind where truth itself is not accepted as the shield.

Jason Feifer: This was welcomed news in places where masks were being worn. In new Orleans, a local order to wear masks was immediately cast aside. And the times of Shreveport, Louisiana reported that waiters in restaurants had, "Cast aside the masks and are now breathing freely." Meanwhile, the captain who originally issued the order to wear masks in New Orleans, was, "Transferred to other duty." But surprise, it was fake news. Here was the headline in the Sacramento Bee a few days later.

Voice Clip (Sacramento Bee): Campaign against gauze masks is without facts.

Jason Feifer: It seems, someone sent a fake telegram signed by the surgeon general of the United States and the newspapers all printed it. So what did the surgeon general think about masks? Well, he told the Sacramento Bee that he recommends wearing a mask if you're coming in contact with influenza, but otherwise he said...

Voice Clip (surgeon general): We do not recommend that person's not in immediate contact with influenza cases should wear a mask, but we do not advise against it either.

Jason Feifer: For those keeping track at home, that was the rare triple negative in a sentence. The hat trick of negative. It was as if someone said Mr. surgeon general, are you a person who can bring clarity to this world? And then he said...

Voice Clip (surgeon general): Negative. I am a meat Popsicle.

Jason Feifer: Although to be fair to the meat Popsicle, there just wasn't good science on masks back then. I mean, there wasn't good science on viruses back then. And also, did you catch that surprising word in the headline from the Sacramento Bee, here, let's throw some verbal italics on it.

Voice Clip (Sacramento Bee): Campaign against gauze masks is without facts.

Jason Feifer: Gauze masks. That's what people were wearing.

Voice Clip (surgeon general): There were two-ply gauze. They weren't very effective and gauze was better than some of the masks. Because in an effort to make it more palatable for women to wear masks, there was recommendations said, "Oh, you can make a mask out of chiffon."

Jason Feifer: And people may not have understood much about the virus, but they were getting a pretty good idea of how pointless these masks were. In November of 1918, a group of doctors got together to advocate against the masks. The Salt Lake Herald-Republican reported on some of the highlights of the meeting, including this one.

Speaker 16: Dr. Staffer called attention to the disagreeable futures of masking and said sunshine and fresh air are of far more value as masks are not efficient protection. He suggested that vaccine is far more effective in rendering persons immune.

Jason Feifer: So, that's an interesting snapshot of science, isn't it? When a doctor is like, "Guys, stick with me here. I think a vaccine might be a good idea." Meanwhile, a Dr. Edwards of San Francisco gave testimony about his own experience with masks.

Speaker 16: He said he had a dozen of them and changed every hour, yet he contracted the disease and was sick three weeks.

Jason Feifer: So, that was the conversation happening around masks at the time. Now let's pick up the timeline. Late 1918, the second wave of the virus strikes. And once again, San Francisco is slow to respond. Fatalities sore in November, and December, and into January, which is when the city finally decides to take some action. And...

Voice Clip (surgeon general): They reinstated the mask law on January 17th, but they never reinstated the other measures. The closures, the social distancing measures.

Jason Feifer: Now San Francisco has completed the trifecta of pandemic mismanagement. They reopened the city too early, closed it again, too late, and placed their entire preventative focus on wrapping gauze around your face. And here's when they learned a lesson that we will almost certainly relearn when the second wave of the virus hits us, people might be willing to go along with some preventative measures the first time, but it is really, really hard to get them to do it a second time. And a century ago, that was especially true because the war was over, by that time the second wave hit.

Voice Clip (surgeon general): Once the war had ended, people were weary of being told, "It's your patriotic duty to wear this mask," when they weren't at all convinced that it was effective.

Jason Feifer: So, what happened? Well among other things, the Anti-Mask League happened. This is where we get the Anti-Mask League. It appeared in January of 1919, after San Francisco had experienced months of deaths, and then, belatedly sprung into action with little more than a new law mandating masks. The anti-maskers held a big meeting, and they conducted some activism around the city, and yes, as every story about the Anti-Mask League will tell you, they achieved victory. They played a role in rescinding the mask law on February 1st. But how much of a victory was it, really?

Voice Clip (surgeon general): By February 1st, when that law was rescinded, it had very little effect on the epidemic which had run its course, basically, by that point.

Jason Feifer: So in short, the Anti-Mask League appeared after every possible damage had already been done. Now, this tale does not give me much confidence, because yes, some things are very different between then and now. Our masks are a lot better, our science is a lot better, but if you think back to the things we've heard can make a difference in this episode, say consistent and participatory leadership, lots of compelling data and tactics that do not trigger reactants, well, we are not doing much better in 2020 than we did in 1918.

It's a depressing way to look at it. But, I do have a glimmer of hope. Because in the face of everything that's happening, all of this chaos, all of this disagreement, do you know who's wearing a mask? Do you know who was told to wear a mask? Whose state government has mandated that he wear a mask? And who is actually wearing the mask? Well, it is Mr. seat belt himself.

David Vittone: My daughter in an RN, she's on the front line and she said, "You should wear the mask. You're old enough to die from it dad. Come on, don't be an old fool. Wear the mask." "Yeah. Okay. It's all right. I'll wear the mask. But I'm not going to wear the mask driving around."

Jason Feifer: Dave, we would expect nothing less. And you know, I, oh, wait, he's got more to say.

David Vittone: I don't like the guys, yelling in the face of the police, and I'm not wearing a mask because it infringes on my right to get god damn haircut. It's ridiculous. That seems ridiculous to me, "Just shut up and with a mask on. Come on."

Jason Feifer: Right. So anyway, I was like, oh wait, he's still going.

David Vittone: Ah, the country's shut down the economy, but I think it's a nice break. I like it. What other interesting thing's going to happen? Where's the asteroid? How about the alien invasion? Come on, zombie apocalypse? It's almost exciting. It really is almost like being in a disaster movie. Tell me if... Yeah. Cool. Me and Tom Cruise [crosstalk 00:39:16]

Jason Feifer: See, I told you that guy can talk. So, here's what I take away from all this. People may not like being told what to do, and they may not trust something they cannot see or understand, but they do respond to trust. I mean, Dave was told to wear a mask and Dave hates being told what to do, but he's listening because the mandate came from someone he trusts. It came from his daughter.

I mean, it also came from the government of Massachusetts, but I doubt that matters much to him. His daughter, however, does matter. This seems to be our override. This is our primary protection. We seem born with reactants, born with the sense that nobody can tell us what to do, but we have a fail safe. We have some way, equally, built into us. Equally as biological that we can save ourselves from ourselves. It is trust.

It's listening to those we truly believe no more than we do. And if necessary, we are willing to bet our lives on it. So, how do you create change? You build trust and you do it long before you need to. You start it when lives are not on the line, when there's no agenda, when there's nothing more for you to do than stand up and reveal your purpose. If you're a leader, or a communicator, or an organizer, or just a friend, or family member whose job, or role, or responsibility, or desire is to be helpful, then build and lean on that trust.

Earn it, make it unquestionable, make it pure, because holy crap, in times like these very few people seem to have any idea of what they're doing and that leaves us all, as individuals, to fall back upon the messy, and complicated, and contradictory instincts buried deep inside us. And please, please, if we need anything right now, it is someone we can trust.

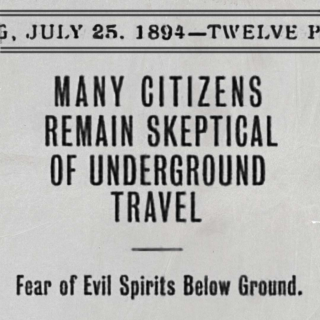

And that's our episode. So, a little behind the scenes look here, at first when I heard about the Anti-Mask League and decided to do an episode on it, I wasn't sure what the episode would be about. Just the league? The history of masks? The history of people opposing medical innovations? Eventually I landed where you just heard, but in the meantime, the team here had gathered some fun stuff from throughout medical history. And one of them really gave me pause. I'm going to share it with you in a minute, but first, do you have an idea for a future episode, get in touch. There are so many ways to do it. You can reach out on Twitter at, @pessimistsarc, pessimistsA-R-C, and follow us there too, because we're always tweeting out the ill-conceived words of pessimists throughout history.

You can visit our website, pessimists.co, which has links to a lot of things discussed in this episode, and also an archive of historical pessimism searchable by innovation. And if you're a fan of Pessimists Archive, then please subscribe, tell a friend, give us a rating or review on apple podcasts. You can really help us grow. This episode was recorded as I sat cross-legged on the floor in my parent's closet in Boulder, Colorado with my foot constantly falling asleep, because the pandemic. Additional research by Louis Anslow and Britta Lokting, sound editing by Alec Bayless.

Our webmaster is James steward, voices by [Jeanne 00:42:17] Maura and [Brent 00:42:18] Rose. Check them out jeannemaura.com, brentrose.com and a special thanks to Irena [Lograf 00:42:23] for her help on video. Watch the internet because videos are coming. Our theme music is by Casper Babypants. Learn more at babypantsmusic.com. Pessimists Archive is supported in part by the Charles Koch Foundation. Learn more about the foundation at ckf.org/tech.

Okay, Like I said, we were rounding up some interesting pessimism from throughout the history of medicine. And this one really got me thinking a lot. In 1839, when anesthesia was very far away from being a real thing the French surgeon, Alfred Velpeau said this...

Alfred Velpeau: The abolishment of pain in surgery is a [inaudible 00:42:58]. It is absurd to go on seeking it today. Knife and pain are two words in surgery that must forever be associated in the consciousness of the patients. Does this compel a story combination? We have to adjust ourselves.

Jason Feifer: I went searching for some context for that quote and discovered a book called, The Wondrous Story of Anesthesia, which made a fascinating point. The authors wrote, "We suggest that the most likely explanation for the delay in the discovery of anesthesia was the belief that it did not, could not exist. If it did not exist, then a search for this dragon would be fruitless." And what a lesson for our times, right? When everything at once feels impossible and suddenly possible, do not ignore the possible just because you think it might be impossible. Our lives are full of the once impossible.

Maybe there's an episode in that after all. I don't know. You'll have to stay tuned. All right. That's it for this time. Thanks for listening to Pessimists Archive, I hope you are healthy and safe wherever you are. I'm Jason Feifer and we'll see you in the near future.

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.