If you’ve ever voted in an election, watched the Bachelor, or worried about the end of days, then you’ve probably fallen for a specific rhetorical trick. In this episode, we explore the history of the phrase “the most important election of our lifetime,” and why the human brain is so UNIQUELY, INSANELY, OUTRAGEOUSLY(!!!) susceptible to hyperbole.

Jason Feifer: This is a podcast about how change happens. I'm Jason Feifer. I'm recording these words in October of the year 2020, shortly before an election that many people, including the candidates often tell us is the most important election of our lifetime. And recently that got me wondering, what is the history of the phrase, this is the most important election of our lifetime? Because we're told that all the time. Everyone has said that this is the most important election of our lifetime in pretty much every election of our lifetime. For example...

Speaker 2: This is the most important election of our lifetime.

Speaker 3: This is the most important election of our times.

Speaker 4: Look, this is the most important election, certainly in my lifetime.

Speaker 5: This is the most important election in our lifetimes.

Speaker 6: This is the most important election of all our lifetimes.

Jason Feifer: If you're hearing this podcast before the first Tuesday in November in the year 2020, then you may agree, this is the most important election of our lifetime, and maybe it is. Maybe it is, I admit it sure feels that way. Or maybe you're listening to this four years from now or maybe you're actually approaching election day 2024. And if that's the case, well, I bet you have been told that your election is the most important election of our lifetime. And I bet that feels true too, I bet it's always felt true and always will feel true. And that makes me wonder, why? Because okay, statistically speaking, every election cannot be the most important, right? I think. I mean, in a way, I suppose it's easy to fact check this, just take 2012 when Chuck Norris unleashed this verbal karate chop.

Voice Clip (Chuck Norris): We're at a tipping point and quite possibly our country, as we know it may be lost forever.

Jason Feifer: That's from a video that Chuck made about the dangers of reelecting Barack Obama, and then Obama was reelected. And maybe you think that was a good thing, and maybe you think that was a bad thing, but was our country as we know it lost forever as Chuck Norris predicted? Birth day 1776, expiration date 2012 at the very least to fact check would seem to confirm that America continues to exist with roughly the same laws and structures as we knew it eight years ago. So Chuck sure can kick a wooden board in half, but I think he's bad at properly identifying the singular tipping point in American history. But again, for enough people, Chuck's words felt very true at the time. The more I thought about this question of the most important election of our lifetime, the more curious I got about everything that it represents. I mean, we must logically understand that it can't always be true. So why do we talk like this? And more importantly, why do we respond to it?

Robert Cloninger: The question you're asking is actually one of the most important questions for our time, but seriously, that's true.

Jason Feifer: This is Robert Cloninger and he is not interested in my question as a question of politics because he is not in politics. He's an extremely accomplished psychologist. One you'll hear more from later in this episode, but when I called him to ask about why we're always willing to believe that we're facing the most important election of our lifetime, he said, this is actually part of a much bigger issue.

Robert Cloninger: Because the way you phrased it, it was meant I think, to help each of us to become aware of how we are manipulated and how we do things that are objectively foolish and we're misled. And why do we keep letting that happen?

Jason Feifer: Because this isn't just a question of the most important election of our lifetime, it's a question about how easily other people can work our emotions. It's a question of how we become so gullible, not just in politics, but in anything in which someone is trying to influence our behavior in ways meaningful and also totally frivolous. And Robert asks the most pressing question there, why do we keep letting that happen? So here's what we're going to do on this, which is of course the most important podcast episode of our lifetime. We are going to start with the history of the phrase and politics, but then we are going to go way past it outward from politics and into culture, into life, into death, into the psychology of it all. And why phrases like the most important are a bullseye into the workings of our brain and how we can become more resilient to that and less gullible too.

Come to think of it, maybe this is the most important podcast episode I've ever made or is that just what I want you to think? So we'll get into it all and while you're listening, you can ponder this fun question, what was the least important election of our lifetime? I've got answers coming up after the break.

All right, we're back. So like I said, this episode is going to begin with the phrase, the most important election of our lifetime, and then get really underneath it to understand the reason we talk this way. And more importantly, the reason we believe it, what can this teach us about how to think more critically, think for ourselves, but first let's see where this phrase actually came from. I did a lot of digging through newspaper archives and the earliest reference I can find isn't exactly the phrase in question, but it's pretty close.

Speaker 9: Today will be held the most important election you have ever been called upon to attend.

Jason Feifer: That is the Philadelphia Aurora newspaper in 1805. And it goes on.

Speaker 9: Today you are to meet your old and uniform political opponents, the Federalists, who are supported by a mongrel faction destitute of all principles.

Jason Feifer: Now, this is the earliest version that I could find. I can't say for certain that it is the literal birth of the construction, the most important election. But I can't say that even in those early days of the phrase and these early days of American democracy, things were getting ugly fast. What you just heard comes from a nearly full page statement from the paper and the most important election in question is the election for Pennsylvania governor, which pitted incumbent Thomas McKean against challenger Simon Snyder, a big portion of the newspaper page is devoted to a side-by-side comparison chart. It's something you still see in partisan political mailings today where voters will get a postcard from some super pack saying, this candidate supports freedom and this candidate supports misery. So just for fun, here are a few lines from that chart in 1805 so you can see if you can figure out which candidate the Philadelphia Aurora editors were supporting. So first we have Simon Snyder.

Voice Clip (Simon Snyder): An independent farmer.

Jason Feifer: And then Thomas McKean.

Voice Clip (Thomas McKean): An interested and prejudice lawyer.

Jason Feifer: Simon Snyder.

Voice Clip (Simon Snyder): Whose understanding is strong and discriminating.

Jason Feifer: Thomas McKean.

Voice Clip (Thomas McKean): Whose understanding is perverted and weakened by passion and intemperance.

Jason Feifer: Simon Snyder.

Voice Clip (Simon Snyder): Who has been a judge without being detested.

Jason Feifer: Thomas McKean.

Voice Clip (Thomas McKean): Who has been so intolerant a judge as to be detested.

Jason Feifer: I mean, you got to go with the guy who isn't detested, right? Wrong, Pennsylvania went for the guy who's detested and he served three terms as governor and all. So onward, we go through the most important elections of all time, which becomes just about every election, large and small. It's interesting, former U.S. speaker of the house, Tip O'Neill had famously said that all politics is local and that really is born out in these most important elections. The earliest days of the phrase are often applied to local races. For example, I found the Greenville Democrats son, a newspaper in Tennessee, which reported in 1913, that...

Speaker 12: The most important election in the history of the country will take place on Thursday, June 21st, day after tomorrow, when Greene County will be called on to vote $200,000 for the purpose of resurfacing the roads.

Jason Feifer: Imagine living in a world where the most important question you're called upon to answer is whether to resurface the roads. But again, we haven't heard the exact magic phrase yet. We heard the most important election in the history of the country and in 1805, we heard the most important election you have ever been called upon to attend. And I found a ton of uses of the phrase, a most important election, which is a nice hedge, and there are many more other stringent variations in the Pittsfield son in 1813, you had...

Speaker 12: The most important election that has taken place since the adoption of the federal constitution.

Jason Feifer: And in the Poughkeepsie Journal 1824, you had...

Speaker 12: The most important election that could occur in the American Union.

Jason Feifer: And in the Vermont Chronicle, 1864, you had...

Speaker 12: The most important election in the history of this nation.

Jason Feifer: And yes, the year 1864 should jump out to you because that was the year Abraham Lincoln ran for and won reelection as president in the middle of the civil war. So maybe the Vermont Chronicle was right about that one, but where can we find the exact words we use today? The words, the most important election in our lifetime? Well, again, I can't say definitively that I have found the very first usage of it, but I did find the very first one in the very robust archives of newspapers.com and it dates back to 1936 in a newspaper called the Herald Press of St. Joseph, Michigan, and little aside here, our episode about the 1907 national moral crisis over Teddy bears also originated in St. Joseph, Michigan, and also quoted from the Herald press, what history there?

Anyway onto the potential birth of a phrase. The year was 1936, Michigan governor Frank Fitzgerald was running for reelection and held a rally where Fitzgerald himself only spoke for three minutes. What a guy? And then he led a parade of surrogates take over. One of them was Michigan secretary of state Orville E. Atwood. And according to the Herald press, Atwood told the adoring crowd this...

Atwood: The issue is whether American ideas are to continue or whether we are to adopt a European regimentation and collectivism. This is the most important election of our lifetime.

Jason Feifer: And there it is the most important election of our lifetime. It's a phrase that defines politics today and was unleashed word for word, at least as far back as 1936, to support Frank Fitzgerald in his run for reelection as governor and just for funsies, you know what happened? Fitzgerald lost. And then he ran again two years later, one. And year after that he got the flu and had a heart attack and became the first and only Michigan governor to die while in office. So that election was, I suppose, at least one of the most important elections of his lifetime, too soon? Sorry. All right. So now we can establish it. Americans have been told since at least a few decades into the country's existence that many or most, or even all of the elections they're called to vote in are the most important. And it makes me wonder why this phrase and why has it endured for so long?

Jim Messina: Well, let me tell you a story that maybe will encapsulate it.

Jason Feifer: This is Jim, and he knows a few things about elections.

Jim Messina: Jim Messina. I was Barack Obama's campaign manager and deputy White House chief of staff.

Jason Feifer: And when Jim was serving as Obama's campaign manager often at around two o'clock in the morning...

Jim Messina: I'd get a call from the smartest political operative in the world, which is Bill Clinton.

Voice Clip (Bill Clinton): Hello, good evening.

Jim Messina: Always in the middle of the night, always woke me up and Bill Clinton would always say, Jim, every presidential election around the world is always a referendum on the future. And if you win that referendum you win the election, if you don't, you won't. And when you start to kind of look back at how people begin to frame that, it has become sort of de rigueur in American politics to make one of the benchmarks for why you should participate into this election has consequences. And it's incredibly important. And some politicians have short circuit of that by saying it's the most important election of our lifetime.

Jason Feifer: And of course Jim's own candidate used the phrase too, but Jim says, Obama didn't really like the phrase. So instead of delivering it straight.

Jim Messina: He also owned up to the fact that that's what politicians always said, and that rhetorical device allowed him to then make the case why this election mattered.

Barrack Obama: Politicians say every time, this is the most important election. This one's really that important.

Jason Feifer: And that, Jim says was actually a more effective strategy than straight up using the phrase.

Jim Messina: It said to the average person, I'm not just going to give you bullshit rhetoric.

Jason Feifer: Because people have heard it before. So by trotting it out, calling BS on the BS, and then still basically making the case that this is the most important election of your lifetime, he built trust with his audience. It sounded like he wasn't just using a line on them even as he just used a line on them. But Jim says, there's another reason this phrase is particularly popular in American elections, perhaps really the most important reason. And that is this, American voter turnout is way below most of the developed world. I mean, just shy of 56% of the U.S. voting age population actually cast a ballot in 2016.

Jim Messina: One of the most effective ways to get people to vote has been to discuss the importance in their personal lives and why this election really affects them. And that's why politicians have used this kind of phrasing before.

Jason Feifer: So in short, the phrase is doing three things. It's raising the stakes, it's creating a bond and it's driving engagement, which when you think about it makes this is the most important election of our lifetime, a lot like a different kind of contest. One where the contestants are just as self-interested, but considerably more attractive.

Speaker 16: The most shocking finale in bachelor history.

Speaker 17: Here's a special look at what promises to be one of the most dramatic and emotional finales ever.

Speaker 19: This season of the Bachelor is an unbelievable journey, like you've never seen before.

Speaker 23: With this new season of the Bachelorette, is like nothing you've ever seen before and it's not because of the pandemic.

Jason Feifer: It's the Bachelor where basically every season is promoted as the most dramatic season of the Bachelor ever. The phrase is used so often that it's kind of boxed show into a corner.

Robert Thompson: If a new episode or a new season of the Bachelor was ever introduced and it didn't tell us it was going to be the most dramatic ever, that would be surprising.

Jason Feifer: This is Robert Thompson, a professor of television and popular culture at Syracuse University. And he says that unlike politics where hyperbole almost immediately became part of the show, television ramped up a little slower.

Robert Thompson: If you go back to the 1950s, you will see promotions for upcoming shows, but it will say things like The Ed Sullivan show, tonight at eight o'clock, seven central Ed's guests tonight are... they were more informational.

Jason Feifer: But that was also at a time where there just wasn't much competition on television. Almost all the programming came from three networks, NBC, CBS, ABC, but future home of the bachelor ABC was running a distant third. So NBC and CBS just weren't sweating it. Then in the 1970s, ABC started to play catch-up and eventually became number one. And that is when networks started to change the way that they promoted shows, trying to convince you that everything was must-see TV and a show was a show that you didn't want to miss. And they'd often start putting together what they called very special episodes.

Speaker 22: Tuesday, on a very special, full house a story of love.

Jason Feifer: But back then, Robert says the networks had a certain integrity to maintain.

Robert Thompson: You couldn't advertise every single episode as being a very special one, but then reality TV comes along and that's pretty much what they did.

Jason Feifer: It happened for a few reasons. One by the time reality TV came along, there was even more competition for people's attention. And of course, that competition continues to grow today. And two, reality TV is super repetitive. A show like the Bachelor does not change, same setting, same format, same pacing, same kinds of people playing the same roles.

Robert Thompson: It's the same program over and over. So it really relies upon the drama coming in from the nature of the people who they've cast and how they behave or more importantly, how they misbehave.

Jason Feifer: So the drama is the only thing to advertise, but here's where it gets interesting. You might think, okay. If every season is advertised as the most dramatic season of the Bachelor ever then regular Bachelor viewers must often disagree, right? What if last season had way more tears and shouting than this season won't they feel duped? And Richard said the answer is no, because sometimes, sometimes the promise does pay off.

Robert Thompson: I remember the very first Bachelor, when it came out in the early part of the new millennium, kissing one of the people on there was still a big deal back then. And oftentimes you'd go episodes before that would happen.

Jason Feifer: That first season was like a sexually repressed Victorian wedding compared to the new seasons. The stakes do get raised. Not always, not every time, but it does happen. And if you can pay off on the claim one time, then you can make the claim every time, which is kind of like elections. And also weirdly kind of like this.

Bradley Garrett: There was one period in the history of our species where we were down to about 100,000 people. We almost went extinct at one time.

Jason Feifer: That is true. By the way, I had to look it up. It turns out it's known as the Toba catastrophe theory dates back to a volcano that exploded in what we now know as Indonesia about 75,000 years ago, led to a massive global cooling during what was already an ice age and nearly wiped out the homosapiens. And that guy you just heard has spent a lot of time trying to understand why people are motivated by stories like that.

Bradley Garrett: My name's Bradley Garrett. I'm a social and cultural geographer at University College Dublin. And my most recent book is Bunker: Building for the End Times, I spent the past three years doing research with doomsday preppers around the world who were preparing for the end of days in various ways.

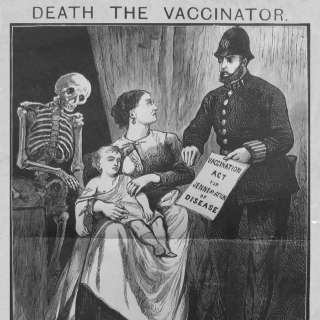

Jason Feifer: Okay. Let's hit pause here for a second. So I can explain why I just took you from hyperbolic campaign language to the Bachelor, to Bradley talking about the end of days. So come along with me on a tangent that I promise we'll swing back around. Every so often some group of people, and sometimes many people believe that the world is about to end. It is common that there's literally a Wikipedia page called list of dates predicted for apocalyptic events. And it is a long list. The first one is the year 66' when a Jewish Samaritan sect from the time thought that an uprising against the Romans was the final end times battle. Then you fast forward to the year 65' when a French Bishop announces the end of the world. And there's pretty much a end times prediction every 20 to 50 years after that, up until today. The loudest one during our own lifetimes was back in 2012, maybe you remember it. It was the end of the Mayan calendar and it led to stuff like this

Speaker 24: World leaders and scientists scrambled today to say, the end of the world is not near here's ABC's David Bright.

David Bright: The ancient Mayans are now a problem for NASA. The space agency has received so many panicked calls about the Mayan apocalypse. They put out a video to reassure people.

Jason Feifer: And I don't know about you, but every time I hear some doomsday prediction, I think this, consult the statistics. I mean, even if you began with the premise that the world will end and not in 5 billion years, when the sun enters its red giant phase, but abruptly in the middle of the civilization as we know it well, even if that were the case, what are the odds that you are alive to see it? Consider the numbers. We as individuals are alive for such a very small slice of human history, homosapiens developed modern human behavior around 50,000 years ago. And how long does the average human live for? It's hard to average out across all of time and culture, but for whatever it's worth, the human lifespan in pre-modern times was thought to be about 30 years and now it's as high as 83 years if you live in Japan. So purely for the sake of argument, let's say the average life span across time is 50 years.

So 50,000 years of humanity broken up into a string of 50 year segments. You have a 0.1% chance of being alive during the 50 year segment when the apocalypse comes. And that's assuming the apocalypse happens sometime between the beginning of our species and right now, which of course it hasn't happened. So now we've got to add years. What if human life, as we know it, goes on for another 50,000 years, we don't know maybe it will. And then we're colonizing planets like Star Trek. And one day someone's like the end of the world is here. And you say which world and the person says earth. And you say, what? That old thing?

Anyway, percentage chance of you being alive at that moment, 0.05%. My point is we have to really flatter ourselves to think that we are alive and unprecedented or even critically important times that our time, our spec on the continuum is the moment when the continuum itself changes. But you can see why that idea is really appealing, right? We don't want to live in unimportant times. We don't want to think that we're not the bulwark that stands between all that is good and all that is not. We would rather think that we guard the precipice of history because it gives our life a kind of epic purpose. I mean, why does Chuck Norris make a video that says...

Voice Clip (Chuck Norris): We're at a tipping point and quite possibly our country, as we know it, may be lost forever.

Jason Feifer: Because Chuck Norris like so many people like to flatter themselves by thinking that they play a role in history. If there is a tipping point, Chuck Norris can stand in front of it. If there's no tipping point, then Chuck Norris might as well go home and destroy a pint of Haagen Dazs. And yet of course, this is where things get complicated because there have been most important elections, just like there have been most dramatic seasons of the Bachelor ever. And there have been terrible, terrible calamities and wars that have killed millions of people, which brings me back to Bradley Garrett, again, author of Bunker: Building for the End Times.

Bradley Garrett: There was a famous speech in 1961 where Kennedy essentially told everyone to go build bunkers in their backyards because the government couldn't afford to protect them. And that sparked a lot of fear in people. And also I think a sense of betrayal. One of the primary functions of the government is supposed to be to protect its citizens. And when people realize that that wasn't going to happen, they started taking matters into their own hands.

Jason Feifer: And that makes sense. I get how that can leave a lasting impression, passed down for generations. Bradley says the majority of preppers don't actually think the world is ending. I mean, some do, but most just want to escape a potential temporary disaster.

Bradley Garrett: They were just putting things in place that made them feel that they had a little bit more control over their lives at a time when I think many of us feel like we don't have control over much.

Jason Feifer: And that is why potentially crazy as it sounds, I see all of these things as related the elections, the pop culture, the doomsday predictions, because they are all in some way or another about exploiting the maybe. They're about pointing to something that has happened in the past and then moving or motivating or manipulating people by convincing them that because it happened before it is happening right now. And it is hard to know how to respond to this because Hey, when the president of the United States says to build a bunker to avoid nuclear war, that sounds pretty legit. But how do we stop ourselves from reacting the same way when well, here's that same ABC report about the end of the Mayan calendar in 2012.

Speaker 22: These backyard bunkers cost $100,000 installed.

Speaker 23: How many of these things do you sell?

Speaker 26: Last year it was one a month. And then since December, it went to one a day.

Jason Feifer: Sometimes it's real and sometimes it's not, but it can feel the same and be presented the same based on the same argument and premise on the same fears. And to make things even more complicated, sometimes a massive change really does happen. And it is a good thing, not a bad thing. Go back 100 years in many men would have been hysterically talking about the tipping point of women being educated and entering the workforce. And they were right in one important way, it was a tipping point. They were witnessing a tipping point and generations later we are thankful for that tipping point, thankful for that change and for the people who made it happen, not for the people who stood in its way. So how do we make sense of this? If we are always being told that now is the moment of great change and now is now or never. How can we tell the difference between something that is important and something that is manipulative? Something that's good and something that's not. Well, remember this guy?

Speaker 26: The question you're asking is actually one of the most important questions for our time, but seriously, that's true.

Jason Feifer: He's a doctor who has spent his career studying how people think to understand exactly this problem. So let's pop the hood on our brains and see what we can find coming up after the break.

Jason Feifer: All right, we're back. So quick recap, campaign rhetoric, television promotion, doomsday movements. What do they all have in common? They all appeal to us by promising something new and critical, and we seem to be very bad at figuring out what's true and what's false. So I wondered what is going on inside of our heads. These messages are clearly exploiting some weakness inside of us. What is it? Well, it is time for a formal introduction.

Robert Cloninger: I'm Robert Cloninger. I'm a psychiatrist and a geneticist and a psychologist.

Jason Feifer: Robert is a professor emeritus at Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis and has spent his career studying personality. It's biological basis, it's psychology and its development. And he's been doing this...

Robert Cloninger: In order to try to understand processes, what captures our interest in complex things. And also what inhibits our response to those situations.

Jason Feifer: And Robert says that this is important because people have a big problem. We are often very bad at recognizing when we're being manipulated.

Robert Cloninger: So the average person is simply emotionally reactive and not very mature in self-control and not self-aware of how they really want to accomplish things that are truly important to them. And so they substitute what other people and advertisers and demagogues promise them like a young child who's immature and easily misled and influenced.

Jason Feifer: But Robert says it does not have to be this way. So let's take a quick peek into our brains.

Robert Cloninger: I've mapped all the genes for human personality, 1,000 genes that we know how they're organized and networks and how they influence learning and memory.

Jason Feifer: This work has helped him to identify three distinct systems that we as humans have that influence learning and memory. We need these systems to be working in harmony, and we need them to be integrated when they're not, we are in trouble. So let's briefly walk through each of them. The first is the habit system.

Robert Cloninger: Let me summarize the way it's necessary to think about it.

Jason Feifer: Sure.

Robert Cloninger: Each of us has certain emotional drives that lead us to have habits that we try to satisfy. But one of those is a predisposition to avoid things that frighten us, that are not rewarding, that are unfamiliar. And there are some people who are very shy, very inhibited, and there are noticeable in their tendency to be worried pessimists, but at the same time, there's another trait, another emotional drive that we also all have. And that is an interest in things that are new and complex that signal us an opportunity to change, which can be something that we're curious about or interested in. And that requires us to begin new kinds of actions. And so these two drives want to inhibit our response to things that are unfamiliar and another that attracts us to approach the unfamiliar, the curious, mysterious are always competing and people vary in the strength of those two drives.

Jason Feifer: You can think of your habits and therefore your actions as a result of this tension, we are always being pulled between a fear of the new and a curiosity of the new. It's why change is such a complicated subject for us. We can at once be resistant to change and also embracing of it. And the result of that tension determines what we do with ourselves. So if you have a strong fear of the new, but also a strong interest in the new, you might develop a set of interests that provides this sensation you're seeking, but from distance.

Robert Cloninger: And that may, for example, lead you not to be a daredevil or a skydiver or an adventurer, but someone who writes novels.

Jason Feifer: Because novelists, these are anxious people. I know quite a few of them. So that's the first system. The second system is more straightforward.

Robert Cloninger: A system for intention and acquisition of facts that allow us to set goals.

Jason Feifer: I like that word intention a lot. It's not just about identifying facts, but it's about being intentional about facts, take in information and make goals based off of it. And then we have one more the system.

Robert Cloninger: The third system allows us to be self-aware.

Jason Feifer: Am I being manipulated? What is my current emotional state and how are my actions being driven by that? This is the third system that influences our learning and memory. And here's the thing about these three systems. Robert says that some of this is very animalistic and some of it is very human, our system of harm avoidance and how our habits and behaviors are born out of what we fear and what we don't that is downright reptilian, our ability to identify things that are provable and true. I mean, a dog can do that. These are old systems deeply inside of us, but the third one Robert says the one about self-awareness, where we can recognize how our emotions impact our decisions, that's not as simple.

Robert Cloninger: What really distinguishes humans from all other animals is this capacity for self-awareness that can be nurtured, but sometimes isn't. And it's not particularly being nursed in our society today to our, I think misfortune.

Jason Feifer: Can I restate that back to you to make sure I understand. So if we're talking about different systems, the system of self-awareness you're saying is the one that is, I mean, obviously our ability to be self-aware is something that is built within us biologically, but the actual refinement of it requires a level of focus as we develop into more mature people but the other systems don't really require as much, the ability to kind of react against danger or to a system that kind of seeks out new. These are things that are... you don't really need to be taught these things. I mean, you can refine them but they're just sort of part of us, but the actual ability to be self-aware and to be critical of our reactions is something that we need to be trained to do. And that's the distinct nature of that system compared to the others. And that's what we don't necessarily focus on teaching ourselves to do, do I understand that correctly?

Robert Cloninger: That's very well said. I'm going to pick on one word you said and I'll explain why. Actually you stated the overall perspective very well. And I think one point is that I wouldn't want to use the word train because training sounds like instruction and conditioning. And what has to happen is to create the conditions in which the person can begin to feel the freedom to explore and to discover for themselves and to think for themselves and not to just do what they're told they should do obediently and so on. And so we found that in prospective studies from childhood into middle adulthood, up to say from age three to age 16, that there are certain conditions that are necessary to really have a creative self-awareness. And that is that you need to have been positively nurtured with love and warmth. You need to have been given the freedom to make mistakes when it's reasonably safe, so that you can learn to think for yourself and not depend on what other people tell you to do, or just on your habits and your customs.

And so these conditions are not a matter of training, but of nurturing and encouragement. And when you raise people under conditions of fear and you don't give them accurate information to process, they don't develop confidence that they can face reality and do effective problem solving. And they lose that sense of wonderment about what's new and mysterious and complex that can be healthy.

Jason Feifer: But that's not to say adults cannot improve themselves. Robert says they can. It requires spending a lot of time understanding why we react to the things that we do. And Robert runs a nonprofit called the Anthropedia Foundation. That's anthro, for human pedia, for teaching a little lesson in ancient Greek for you there. These are centers around the U.S. and Europe. And the idea he says is to teach people how to be the full humans they're capable of being, helping people overcome trauma or personality disorders or whatever. The foundation developed a lot of mind, body exercises, they run meditation centers. They teach people to be wellbeing coaches. And I tell you all of this as a way to say the change he's talking about of developing an underdeveloped system of self-awareness, it takes time and work, but it can happen. And also you can do it in little ways without even taking on some big project and going to some foundation.

For what it's worth, here's one little thing that I started doing a few years ago to protect my own system of self-awareness. I used to follow a lot of political reporters on Twitter, which meant that whenever a politician or pundit did something outrageous, I'd read all the tweets and then I'd read all the stories. And then I get all worked up. And a few years ago I realized, what a waste. I am losing hours of my day, getting in heated imaginary arguments with idiots on cable news. I mean, the idiots on cable news said, whatever idiotic thing they said just so that I would waste half my day getting in heated, imaginary arguments with them. When I am upset, they win. So I unfollowed all of the political reporters. Now, whenever I see news about someone doing something stupid, I basically ignore it. And that decision is what the doctor ordered.

Robert Cloninger: For us to be healthy and happy and not to be just led by the nose. We have to be aware of how people push our buttons and exploit our drives and desires and fears. And at the same time, most people believe that their perspective is the right one. And that even if other people don't really agree, it's a good thing to use whatever means possible to manipulate others, to get them, to share their view.

Jason Feifer: Okay. To appreciate the fullness of that observation, let's do a little thought experiment. Remember how earlier in this episode I said that phrases like the most important election of our lifetime work because there have been most important elections and same is true with the Bachelor and with end of days. If something happened in the past, then we could be convinced that it's happening now. But let's counter program that, can we prove to ourselves that least important things have happened in the past. Well, we can start by identifying the least important election of our lifetime. Remember I promised to offer an answer to this at the very beginning of the show. So do you have one in your head because this guy showed us.

Jeff Greenfield: I'm Jeff Greenfield, I've spent my life covering mostly American politics for the series of TV networks.

Jason Feifer: ABC, CNN, CBS, PBS. And now he's a columnist to Politico magazine. And back in August, Jeff wrote a piece headline, the least important election of our lives. So what was it?

Jeff Greenfield: To me the answer is absolutely clear, it's 1996, when Bill Clinton was reelected and defeated Bob Dole, the Republican nominee.

Jason Feifer: Why? Well, take a trip back to those heady days of 1996.

Jeff Greenfield: 1996 was a hotbed of rest rather than unrest, the economy was in great shape. We were heading toward full employment. There was no inflation. There was real economic growth. Real incomes will be getting to rise and hard it is to believe, the government was beginning to run big surpluses. It looks like over the next decade, we were going to have something like $5 trillion in budget surpluses.

Jason Feifer: By contrast, the U.S. budget is currently running a deficit of 3.1 trillion. So back in 1996, the big debate was what to do with all that money. Meanwhile, the cold war it ended, nobody had heard of Al Qaeda let alone ISIS, both candidates were moderate and the campaigns themselves were fairly drama free. Oh, and the conventions?

Jeff Greenfield: The highlight was one night when women who've been appointed to significant positions in the Clinton administration came out and led the delegates in a rendition of the Macarena.

Jason Feifer: Now of course, plenty of drama would unfold in the second Clinton administration. But back then when people were asked to go to the polls and think about whether they approved or disapproved in the Macarena...

Jeff Greenfield: There wasn't that much, it seemed to be a stake.

Jason Feifer: So give it all that. Did anyone at the time, declare Clinton Dole to be the most important election of our lifetime? Well, yes, on both sides in May 1996, this cookie guy in Vermont named Bernie Sanders, who was announcing that he was running for reelection in the U.S. house of representatives declared that. "I have no hesitation in saying that this is the most important election in our lifetimes and an election in which the choices have never been clearer". And a few months later in September 1996, Ralph Reed of the Christian coalition told his audience that, "This is the most important election of our lifetime". I tried to find audio of those talks, but I couldn't, both of those quotes were found in associated press articles from the time. But I did find this speech that Ralph Reed gave just a few days before the election titled the Christian coalition's view of the election in which he made the case that this wasn't just the most important election of our lifetimes, but our future lifetimes too.

Ralph Reed: We are here, of course, 12 days before the last presidential election of this decade, the last election of this century. And indeed for the first time, since the first Europeans landed on this continent 400 years ago, the last election of a millennium. And so we choose not only the leaders for the next century, we choose the leaders for the third millennium. That is a unique moment in the history of our country. And if you look back at the history of America, it is the last election of a century that always sets the tone and the priorities for the coming century.

Jason Feifer: That's a cute riff, but I mean the election of 1796 was one by John Adams who continued the Federalist policies. And rather than that, setting the tone for the next century, it came to a screeching halt when he lost the next election to Jefferson and 1896, William McKinley won. And to make the case that he defined the next century, you'd have to say that his primary role was to get assassinated and be replaced by his vice president, Theodore Roosevelt, who certainly was consequential, but that was not exactly what people were voting for in the polls at the time. So what are we left with from Ralph's history lesson? Well, I'm reminded of what psychologist Robert Cloninger just said. Most people believe that their perspective is the right one, he told me. And so they think it's perfectly fine to use whatever means possible to manipulate others into sharing their views.

We cannot stop people from doing that. If we could, I guess that literally would be the most important thing to happen in our lifetime, but barring that we can only focus on one thing, ourselves. Our self-awareness, our willingness or opposition to someone else's tool, because we are a bundle of contradictions. We fear change and we want change. We prefer what's familiar and we're curious about what's new and we form habits and gather facts and try to make sense of the world as best we can while at the same time, giving ourselves over to people who scramble our understanding of the world to meet their own needs. So I'll tell you what I've started to do just as a way to give my brain a moment to take everything in. When anyone tells me that this is the best or most important or most dramatic or most interesting or most pressing or newest or unprecedented or unique or anything like that, I think false until proven true.

And then I think, well, is it? Because maybe it is true, but I'll decide that for myself and that's our episode, but Hey, it is not the end of least important things that I have to tell you. Maybe Clinton, Dole was the least important election of our lifetime, but what about the least important American election of all time? Well, I have an answer that you and every historian can debate, but first, if you love this show then please subscribe, tell a friend and give us a rating and review on Apple podcasts and reach out. You can contact me directly by going to my website, Jasonfeifer.com, J-A-S-O-N. F as in Frank, E-I F as in Frank E-R.com or you can get in touch, sign up for my newsletter about how to find opportunity in change and more. This episode was reported by me and Brita Lockins sound editing by Alec Bayless.

Our webmaster is James steward. Our theme music is by Casper baby pants. Learn more at baby dance, music.com. The voice actors you heard during this episode where Gia Maura, you can find her at giamaura.com and Brent Rose find him@brentrose.com. And thanks to Pen Named Consulting, Gordon Brought, Johan Norberg, Johnny Rokia, Aaron David Miller, and to the Washington post, which compiled a much longer version of that most important election montage that I played at the beginning. This show is supported in part by Stand Together. And the new book Believe in People by Charles Koch. Believe in People is a surprising take on how you can tackle America's biggest problems in the stories of social entrepreneurs who already made their mark, not just in our history books, but in our cities, our schools, and our country's greatest areas of need the book hinges on a simple premise that could help answer some of society's biggest problems, unite with anyone willing to do right.

From poverty to education to substance abuse, Believe in People follows the stories of people who reached across barriers and borders to everyone's benefit. It's a book about how change happens and how the seemingly small everyday decisions we make can change society for the better. Famed investor, Marc Andreessen called it, "A roadmap for solving our country's biggest problems" Pre-order Believe in People today at believeinpeoplebook.com/pa and gain access to bonus content ahead of it's November 17th publication. All right. So what was the least important election of all time? A few weeks ago, I was on the James Altucher Show talking about this very subject in advance of this podcast that I was making. And James had a theory here is from that episode.

James Altucher: 1924, Calvin Coolidge versus John Davis. And the only reason I'm saying this is, it's between world Wars, where America had gotten a lot more isolationists after world war one. So the issue of war wasn't debatable and Coolidge's party wasn't responsible for World War I. And there was also the 1920s boom times so things were pretty good. Coolidge was also very an honest person. He replaced Warren G. Harding who was corrupt and died in office. And then finally, both John Davis and Coolidge were conservative politically so conservative and so similar in their issues that Robert LaFollette became kind of this socialist third party candidate, because there was no alternative to the conservative views that both major candidates had.

Jason Feifer: Agree? Disagree? Let me know. That's it for this time. Thanks for listening. I'm Jason Feifer and we'll see you in the near future.

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.